La fiorentina col samovar. Dramatis personae

The Florentine with the samovar

Firenze le pareva bellissima. L’unico posto al mondo dove coltivare i giochi e i sogni. Non Napoli ostile, estranea e chiassosa, la città del clan familiare acquisito. Non Buenos Aires, patria della madre assente da sempre.

Non la Russia che aveva molta parte nei suoi complicati incroci di sangue. Firenze: territorio suo, per nascita e convinzione.

Aveva un viso perfetto. Ed una figura da dea india che lasciava senza fiato. Un’apparizione. Bellissima, troppo per essere vera. A volte la si toccava per credere; c’era.

La conobbi quando era moglie di un amico, Ernesto Porta, docente di radiologia; e madre di quattro figli. Allora vestiva di colori pastello, calzava ’ballerine’ piatte col complesso dell’eccessiva altezza, portava i bellissimi capelli nero-blu tagliati come usava negli anni sessanta. Una fiorentina esportata a Partenope, una signora della ricca borghesia che usava il samovar.

Ma non era come le altre compagne di medici ricercatori della Clinica medica di Napoli. Mentre noi si giocava a poker, per esempio, lei dormiva sui divani. Era arrivata in Via Orazio, giovanissima, direttamente dal collegio. Aveva sposato Ernesto per un colpo di fulmine.

A lui, diretto a Stoccolma, si era bucata una gomma della Ferrari davanti al cancello dell’Istituto per ragazze molto per bene; e lei era lì.

Non si quietava come le altre. Voleva capire la musica da camera, quella lirica, i libri e i quadri. Componeva con la chitarra. A volte mi chiamava a Milano perché le scrivessi dei versi.

Nei primissimi anni settanta arrivano la Svolta e l’oggetto attraverso il quale realizzerà un’esistenza nuova e del tutto diversa: la macchina fotografica. Ha dedicato, Verita Monselles, il suo lavoro al femminile o all’ombra del femminile!

Non direi. Nella sua produzione vanno privilegiati tre filoni, dove si è distinta con voce propria: la ritrattistica; la documentazione sui Magazzini Criminali; le prime foto di paesaggi, passanti, coppie in amore; diciamo le sue incursioni nel territori della vita.

Sempre attenta alla bellezza fisica, al tic e all’inquietudine del soggetto ritratto ma con garbo, con felpata, cordialissima e, a volte, sottilmente scherzosa partecipazione. Con l’umiltà di chi è nata col cappello.

Nel 1969 lei stessa scriveva che aveva incominciato “a seguire il lavoro di fotografi amici, a imparare la tecnica e la ripresa fotografica […] la fotografia mi aiutava ad uscire dal mio ristretto mondo individuale e mi portava fuori, in un mondo vasto, con altri tipi di esperienza sodale e altre emozioni”. I Magazzini Criminali, ecco.

Il punto è che Monselles aveva un occhio assolutamente teatrale – anche i ritratti lo sono – i paesaggi interpretati come scenografie. La sua produzione, in particolare quella della militanza femminista, e penso a Paolina, alla sposa sull’inginocchiatoio, alle bambole bouquet, ecc. testimoniano della sua tendenza a concertare finzioni e illusioni.

Una escogitazione teatrale. Ha rivestito persone ed oggetti di luminosa falsità, come luccicanti di luci da palcoscenico. Condiva il suo oggetto di tutte le seduzioni possibili: armonia, retorica, eleganza, liturgia sociale e mondana. Anche davanti ai ritratti non si pensa subito a donne ed uomini ma a ruoli, a parti, a visioni del copione che aveva in animo.

E lo sguardo luminoso è sempre a metà tra l’ascetico e il sensuale in modo da rifiutare la corruzione del tempo. Come se una patetica ironia, certo sentimentale, facesse da colonna sonora, fluttuando intorno alle immagini: la più parte maschere, persone, anzi dramatis personae.

Le sarebbe piaciuto, oh, sì!

-

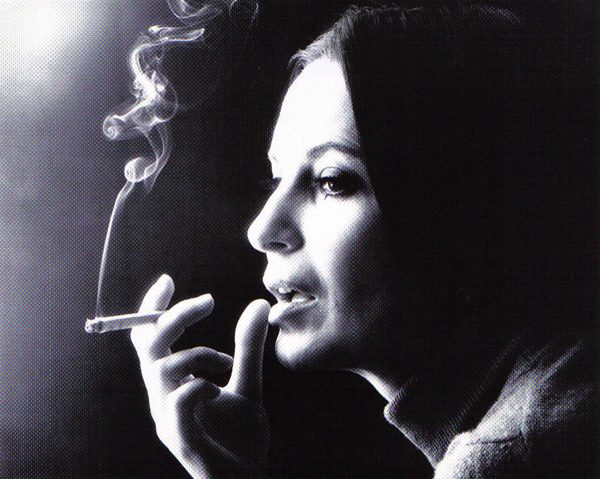

Verita Monselles, ritratto di Lea Vergine

Florence seemed beautiful to her. The only piace in the world where she could cultivate games and dreams. Not the hostile, foreign and noisy Naples, the city of her acquired family. Not Buenos Aires, home of her mother. Not the Russia that played a large role in her complicated bloodlines. Florence: her territory by birth and conviction. She had a perfect face, and the body of a Hindu goddess that would leave you breathless. An apparition, too beautiful to be real. Sometimes you touched her to believe that she was there.

I m et herwhen she was the mother offourchildren and married to a friend, Ernesto Porta, professor of radiology. She wore pastel colors, and fìat ballerina shoes because of her complex about being too tali; she wore her beautiful blue-black hair cut in a sixties style. A Fiorentine exported to Naples, a wealthy bourgeois lady who used a samovar.

But she was not like the other wives of the research physicians at the Clinica Medica in Naples. While we played poker, for example, she slept on the couch. She carne to Via Grazio when she was stili very young, straight from boarding school. She married Ernesto out of love at first sight. He was on his way to Stockholm and got a fìat tire on his Ferrari – right in front of the gate of that school for very respectable young ladies; and she was there. She didn’t keep quiet like the others. She wanted to understand chamber music, opera, books and paintings. She played the guitar. At times she would cali me in Milan asking me to write lyrics for her music.

The Turning Point and the object with which she would create a totally new and different existence – the camera – carne in the early 1970s.

Did Verita Monselles dedicate her work to the femmine or to the shadow of the femmine?. I can’t say. Her work favored three main themes in which she distinguished herself with her own voice: portraiture; the documentation on Magazzini Criminali; the early photographs of landscapes, passersby, lovers, let’s cali them her forays into the different areas of life. She was always aware of physical beauty, the subject’s idiosyncrasies and restlessness; and portrayed them with grace, with a soft, cordial and sometimes subtly playful participation. With the humility of one who was born wearing a hat and gloves. In 1969 she wrote that she had begun “watch photographer friends at work, to learn the techniques and how to shoot […] photography helped me come out of my narrow little world and led me into a vaster one with other types of social experiences andotheremotions”.

Magazzini Criminali. Monselles had an absolutely theatrical eye – even the portraits are theatrical; the landscapes are interpreted like sets. Herpictures, specifically those of the feministactivists, and I think of Paolina, of the bride at the priedieu, the bouquet dolls, etc. bear witness to her tendency to harmonize make-believe and illusions. A theatrical invention. She clothed persons and things in luminous falsity, as if they sparkled from the glow of footlights. She enhanced her subjects with ali possible seductions: harmony, rhetoric, elegance, social and sophisticated liturgy. Even looking at the portraits we do not immediately think of women and men, but of roles, parts, of visions of the script they held in their souls. And that luminous gaze is always midway between the ascetic and the sensual so that it rejects the corruption of time. It is as if a pathetic – and definitely sentimental – irony provided the sound-track, fìuttering around the images: mostly masks, persons or rather dramatis personae. She would have liked it, yes indeed!

Traduzione di Julia Weiss

Pubblicato in occasione della mostra

“Codice inverso, La dissacrazione dell’archetipo maschile nella fotografia” di Verita Monselles, 1970 – 2004

a cura di Lara-Vinca Masini

Prato, Le Antiche Stanze di S. Caterina, 3 -26 giugno 2006