November 28, 1988

MAJOR RETROSPECTIVE OF CZECH PHOTOGRAPHER JOSEF SUDEK OPENING AT THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART

“Everything around us, dead or alive, in the eyes of a crazy photographer mysteriously takes on many variations, so that a seemingly dead object comes to life through light or by its surroundings….To capture some of this–I suppose that’s lyricism.”

Prague and the Bohemian countryside, friends’ backyards, and the simple domestic objects of his home and studio, are all part of The Magic Garden of Josef Sudek, on view at The Cleveland Museum of Art from December 7, 1988 through January 29, 1989. This retrospective exhibition presents one hundred works–conveying a poetic, sometimes surreal atmosphere of mystery and enchantment–by the most important Czechoslovakian photographer of the twentieth century. Widely known and admired in his homeland, the work of the shy and modest Sudek–who seldom left Prague–has been recognized in Western Europe and the United States only recently, with a major exhibition at the George Eastman House in 1974 and the first American monograph of his work published in 1978.

Josef Sudek (1896-1976) was born in Kolin-on-the-Elbe in Bohemia. As a young man he was apprenticed to a Prague bookbinder. During World War I, while serving in the Austro-Hungarian army, he lost his right arm, and could not return to practicing his trade. He turned instead to his hobby of photography, studying at the State School of Graphic Arts from 1922 to 1924. In the late 1920s he made his home in a small studio in Prague, supporting his artistic work with freelance photography–portraits, advertising, photographing paintings and sculpture for books and journals.

Sudek loved painting, and was particularly drawn to Caravaggio’s skillful

handling of light and the romantic landscapes of 19th-century Czech painters. He was also influenced by the photography of such Czech contemporaries as his close friend Jaromfr Funke, with whom he founded the progressive Czech Photographic Society in 1924 (a group that believed in the integrity of the negative and opposed manipulation of prints). The emigre Czech doctor, Drahomir Josef RMiela, introduced Sudek to the compelling combination of modernist geometry and pictorial romanticism in the works of Clarence H. White, a native of Ohio who was Ruzicka’s teacher in New York. Sudek’s lifelong passion for music also shaped his work. He often invited friends to listen to classical music from his extensive record collection, and particularly admired compositions by fellow Czech Leog Jangek, whose home of Hukvaldy in Moravia was Sudek’s summer retreat and the subject of his last book in 1971.

Light was virtually the subject of his photography, like a substance in space transforming and animating all of his images indoors or outside–his cluttered studio and his garden, the 14th-century Charles Bridge or 12th-century Prague castle in snow or mist, and the Bohemian countryside in the transitory light of dawn or dusk.

Sudek’s understanding of light and his ability to anticipate the best moment of illumination epitomize the patient, contemplative and transformational character of his work. The result is a magic that is rare in photography and in the whole world of art.

Sudek’s first portfolio, St. Vitus Cathedral, published in 1928 for the tenth anniversary of the Czechoslovak Republic, contained fifteen prints of the famous building (begun 925) and its sculptures as well as workers’ ropes and tools, all characterized by a transfiguring light through the church windows that conveys Sudek’s emotional reaction to the scene. On the Table (1930), an early work in the exhibition, shows the influence of modernism. Two fully open flowers, placed in direct sunlight on a glass table top, appear to float within a silver metal frame; their petals contrast with the severe contours and hard, reflective material of the table’s frame and support while the complex web of lines and shapes includes shadows on the blurry grid of the carpet.

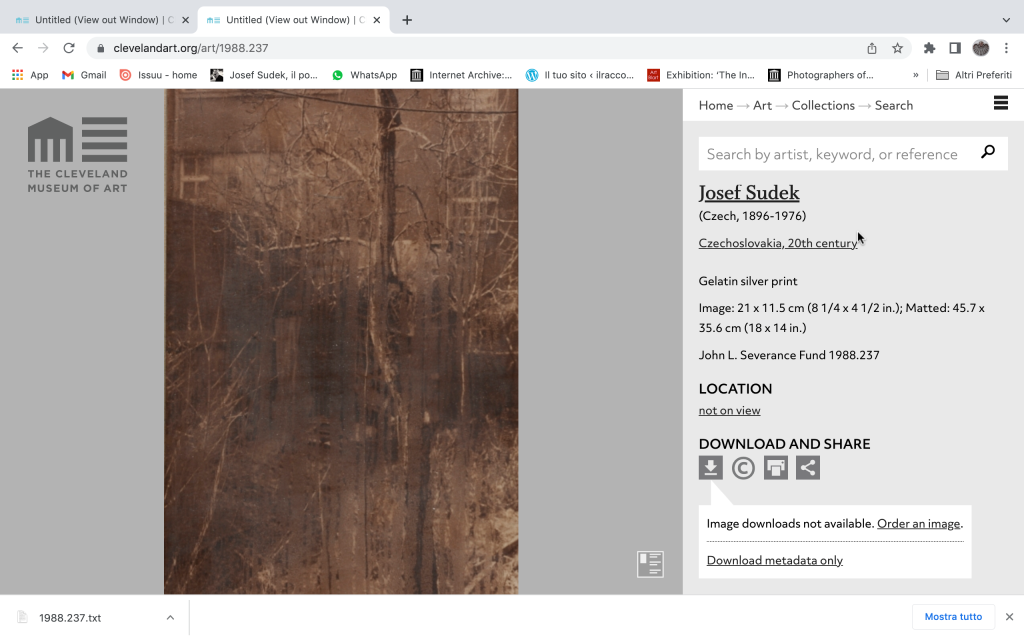

During and after the Nazi occupation in Prague (1939-45), the subjects of Sudek’s work became increasingly private and separate from the world outside his studio. At the same time, Sudek changed his photographic technique and began printing directly from negatives rather than enlarging his images, thereby preserving more accurately the detail and tonal delicacy of his negatives. “Hurry slowly,” his lifelong motto, vividly expresses the character of such later series as The Window of My Studio (1940-54), A Walk in the Magic Garden (1948-64), and The Garden of the Lady. Sculptor (the latter two set in the gardens of his friends Otto Rothmayer, the architect, and the sculptor Hana Wichterlova). Sudek’s mood of intense privacy is often accentuated by the black borders characteristic of contact prints. Many images depict a barrier against the world beyond his studio; in Last Roses (1956), an exquisite, melancholic still life of roses in a glass of water on a windowsill, a windowpane clouded with condensation filters Sudek’s–and the viewer’s–glimpse of the world outside.

The photographer Sonja Bullaty, Sudek’s assistant and close friend, has written that his “life seems to have been guided by the weather, which really meant the light of the seasons.” He photographed mainly from spring to autumn, working primarily inside in the darkroom during winter. Sudek’s fondness for experimentation–particularly with the capabilities of old cameras that used plate or sheet film–led him to produce lushly romantic landscapes using an 1894 Kodak panoramic camera which made 10 x 30 cm negatives.

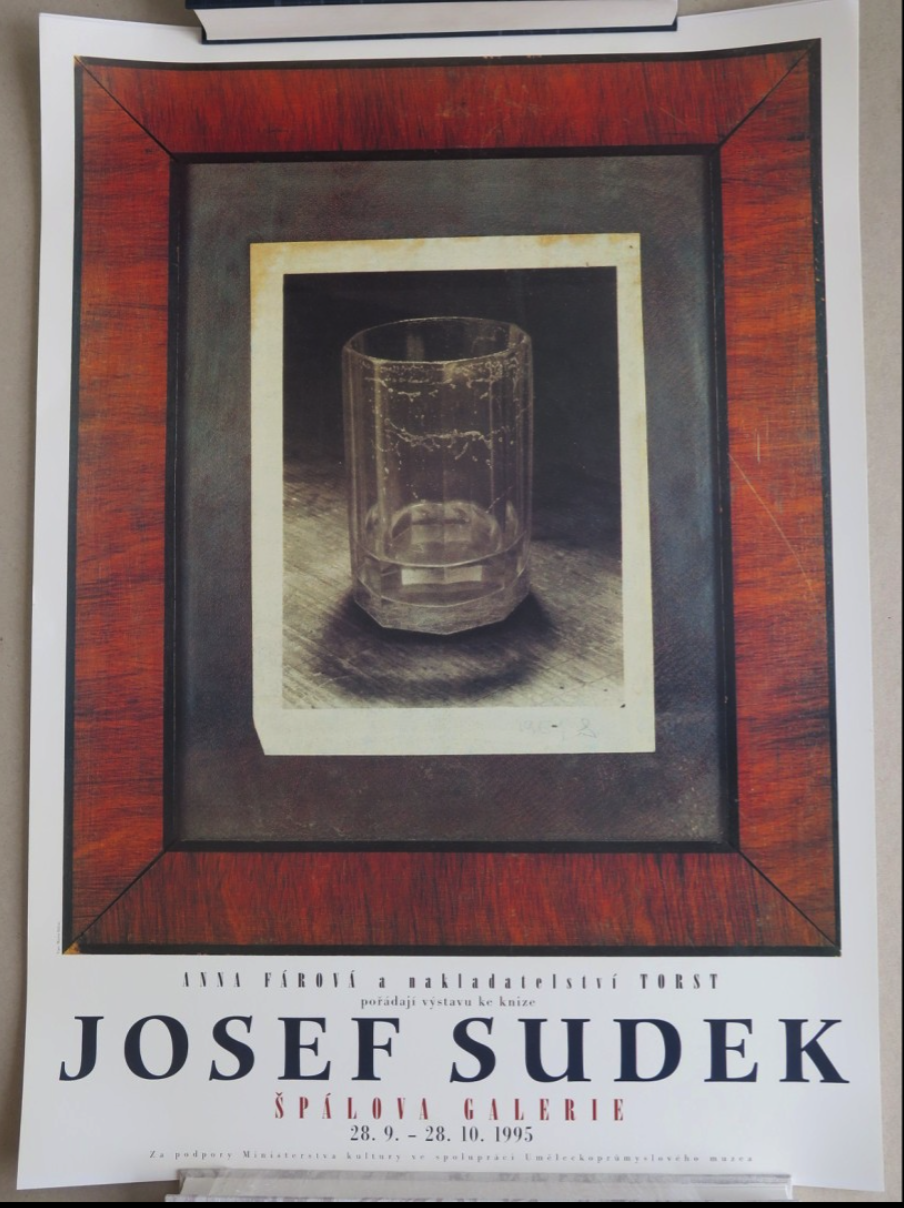

Sudek said, “I believe that photography loves banal objects….I like to tell stories about the life of inanimate objects, to relate something mysterious: the seventh side of the dice.” He evoked the memory of friends with Remembrances (1946-64) composed of objects they had given him. His still lifes of a glass of beer, a plate of fruit, an egg, or a plastic raincoat, often possess an uncanny sense of life, as do his carefully selected Vanished Statues (1952-70) or “sleeping giants”–the huge dead trees of the Bohemian

josef sudek/the cleveland museum of art – and Moravian woods. Sudek’s pictures rarely have a human subject, but the empty chairs that inhabit many of his garden pictures seem just-abandoned or awaiting human visitors.

His photographs often remind the viewer of Sudek’s disability: the landscapes with dismembered old trees; statuary that has picturesquely disintegrated and fallen on the grass. Remembrances of E.A. Poe (1959) incorporates fragmented sculpture along with one of Sudek’s most personal and arresting devices–a glass eye surrealistically staring from the photograph.

These gelatin silver prints are on loan from the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, selected by Zdenk Kirschner, curator in the department of applied graphics and photography. The traveling exhibition was organized by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Socialist Republic, and is presented under the auspices of the ARTS AMERICA program of the United States Information Agency. Katherine Solender of the Museum’s education department will give gallery talks at 1:30pm on December 11 and 14 and January 25 and 29.

# # #

For more information or photographs, please contact the Public Information Office, The Cleveland Museum of Art, 11150 East Boulevard, Cleveland, Ohio; 216/421-7340.